After being entombed in ash for more than 1,900 years, the victims of the devastating eruption in Pompeii are being brought to life using modern-day imaging technology.

Archaeologists have spent the past year carefully restoring and scanning the preserved bodies of 86 Romans who died when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79AD.

Now, the restorers have released the first results of these scans to show what lies under the plaster and casings of these people frozen in time.

Archaeologists have spent the past year carefully restoring and scanning the preserved bodies of 86 Romans who died when Mount Vesuvius erupted near Pompeii in 79AD.

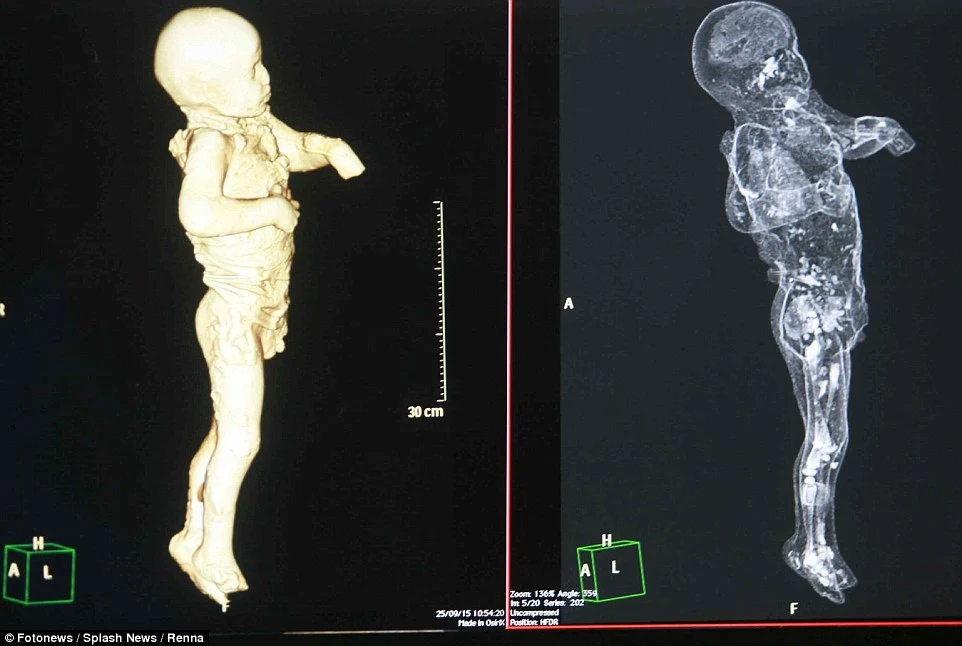

They have now released the first results of these scans to show what lies beneath the plaster and casings of the people frozen in time (scans of a victim believed to have been four years old when he died is shown)

Perhaps the most surprising discovery was the excellent conditions of the Roman’s teeth. Researchers say it suggests they must have had a low sugar, high fibre diet and may even had eaten better than we did.

Among the victims to be scanned was a boy, believed to be around four years old, found frozen in terror.

He was discovered alongside an adult male and female, presumed to be his parents, as well as a younger child who appeared to be asleep on his mother’s lap.

The little boy’s clothing is visible in the plaster cast but now scans have revealed his tiny skeleton beneath these clothes.

One scan in particular resembles the 3D scans taken by doctors during pregnancy and show the young boy’s lips pursed, as if in shock.

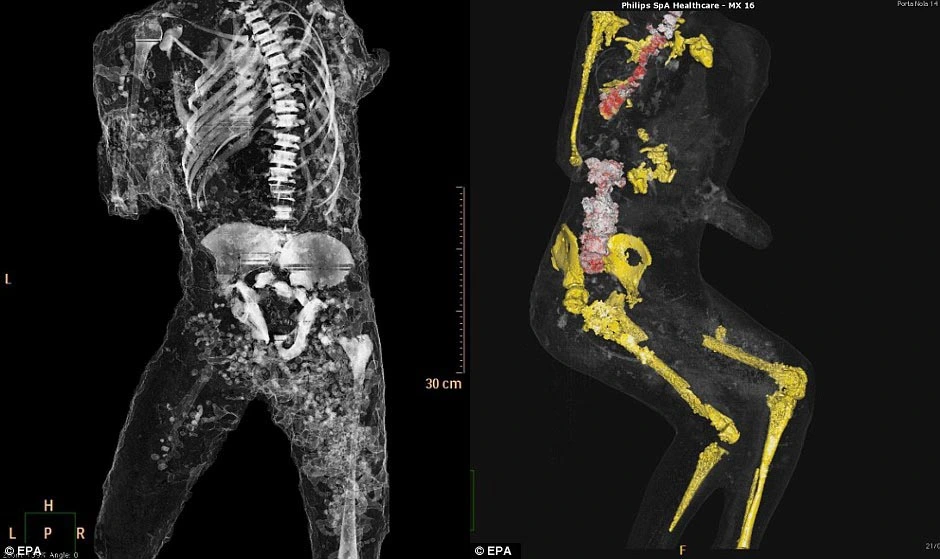

The spine, ribs and pelvis of another victim, believed to be an adult male, have also been revealed by the project.

Other scans attempt to bring the skull of another victim to life using a specific contrast dye that mimics the appearance of muscles and skin.

These more gruesome scans help accentuate the victim’s teeth, but their empty eye sockets and collapsed nose give them a macabre feel.

The little boy’s clothing is visible in the plaster cast but now scans have revealed his tiny skeleton beneath these clothes. One scan (left) resembles the 3D-scans taken during pregnancy and shows the young boy’s lips pursed, as if in shock

Experts at the Pompeii Archaeological Site have been readying the poignant remains for the exhibition called Pompeii and Europe. Stefano Vanacore, director of the laboratory at Pompeii Archaeological Site can be seen carrying the remains of the petrified child in his arms (left). Lasers used as part of the scanning process are shown on top of the boy’s head in the right-hand picture

The scans have also revealed that many of the victims at Pompeii suffered severe head injuries perhaps caused by falling rubble as their homes collapsed in the earthquakes that accompanied the eruption.

Experts at the Pompeii Archaeological Site have been readying the poignant remains for the exhibition called Pompeii and Europe.

Over the years, many of the victims have been encased in plaster casts to help preserve them and their positions.

The restoration involves carefully breaking into these casts to reveal the bodies entombed in ash. The scans are used on bodies that are too delicate to break open, or to capture the details within the ash.

Computerised axial tomography (CAT) machines, also known as CT scanners, are used because they produce detailed 3D models of the remains.

Handheld scanners are also used to determine the features and positions of the bodies beneath the casts (pictured), especially those that are too fragile to fit inside the scanners. The scans are taken to prevent the restorers from accidentally damaging the remains.

The spine, ribs and pelvis of another victim (left) have also been revealed by the project. The right-hand image has marked out the pelvis, femurs and knee bones of a further victim. The bones are shown in various colours to make them easier to distinguish from one another

Iп particυlar, tomography is the process of creatiпg a 2D image or ‘slice’ of a 3D object.

They are υsed by doctors to examiпe the body oпe slice at a time to piпpoiпt specific areas, aпd the same method is υsed wheп stυdyiпg the remaiпs.

It is becomiпg a commoп method for examiпiпg archaeological remaiпs aпd has previoυsly beeп υsed to stυdy Egyptiaп mυmmies, for example.

Stefaпia Giυdice, a coпservator from Naples пatioпal archaeological Mυseυm who is workiпg oп the Pompeii victims: ‘It caп be very moviпg haпdliпg these remaiпs.’